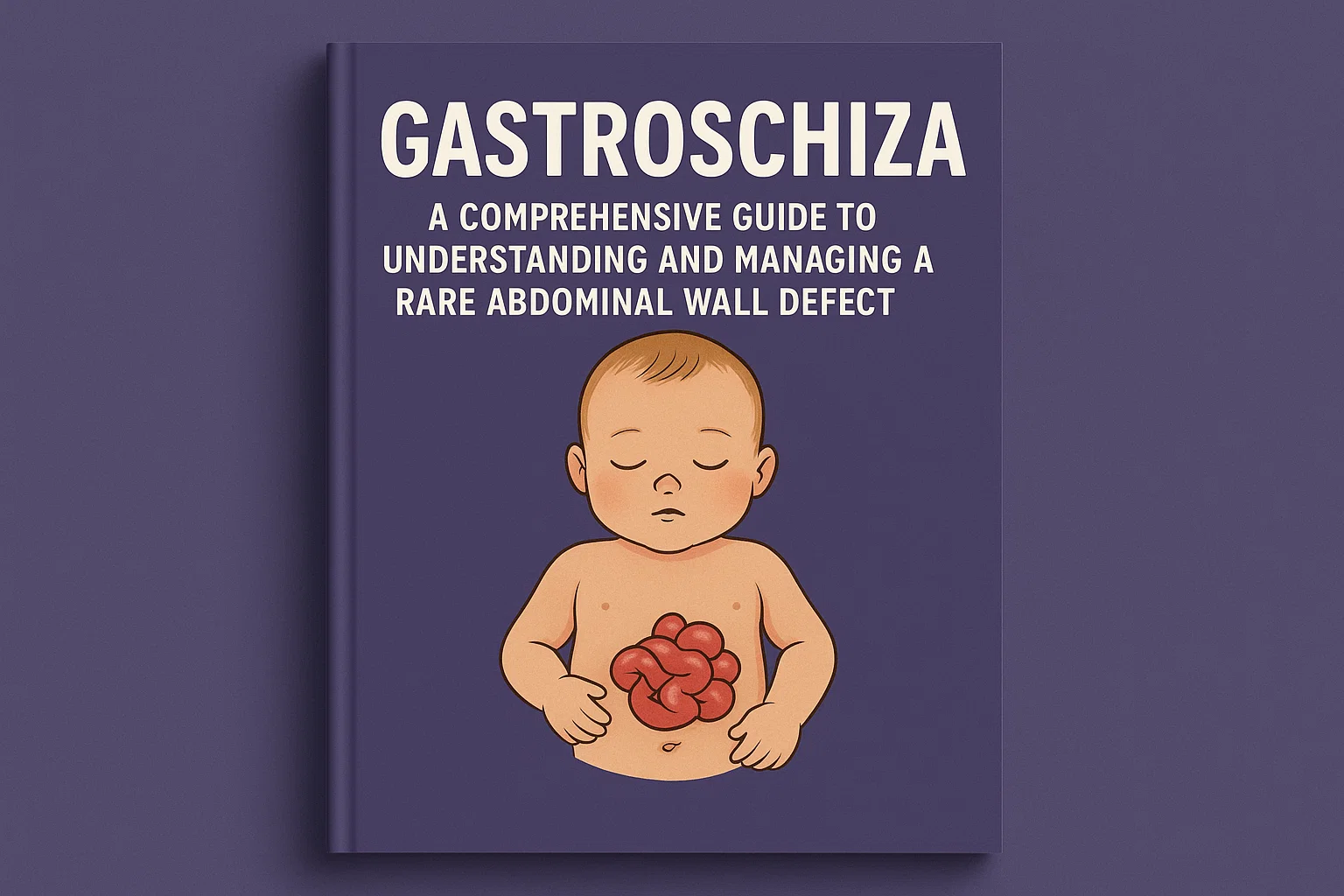

Gastroshiza: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Managing a Rare Abdominal Wall Defect

Bringing a new life into the world is a journey filled with anticipation and joy. Expectant parents eagerly await ultrasound appointments, hoping to catch a glimpse of their developing baby. Most often, these scans bring reassurance and happy news. However, sometimes, they reveal unexpected challenges that require parents and medical teams to prepare for a specialized care journey from the moment of birth. One such rare condition is gastroshiza, a congenital anomaly that, while serious, has seen remarkable advancements in treatment and outcomes.

Gastroshiza is a specific type of abdominal wall defect, often mentioned alongside the more commonly known gastroschisis. It is characterized by a defect in the abdominal wall, typically to the right of the umbilicus, through which the stomach and sometimes other abdominal organs herniate outside the baby’s body. Unlike other defects, it is not covered by a protective membrane, leaving the exposed organs directly in contact with the amniotic fluid during pregnancy. Understanding this condition—its causes, the diagnostic process, the immediate treatment required after birth, and the long-term outlook—is crucial for any family facing this diagnosis. This article will serve as your in-depth guide, demystifying gastroshiza and providing a clear path from diagnosis to recovery and beyond.

What Exactly is Gastroshiza?

To understand gastroshiza, it’s helpful to first picture a baby developing in the womb. During early embryonic development, the abdominal wall forms through a complex process of folding and fusion. In most pregnancies, this process completes seamlessly, containing all the internal organs within the abdominal cavity. Gastroshiza occurs when there is a failure in this process, resulting in a small opening or defect in the abdominal wall. The precise location is almost always to the right side of the umbilical cord’s insertion point.

The key defining feature of gastroshiza is the nature of the herniated organs and the absence of a sac. In this condition, it is primarily the stomach that protrudes through the defect. This is a distinguishing factor from gastroschisis, where the small and large intestines are most commonly exposed. Because there is no protective sac covering the exposed stomach, it is bathed in amniotic fluid throughout the pregnancy. This prolonged exposure can cause irritation and inflammation of the organ, a condition known as chemical serositis, which can make the stomach appear thickened, matted, or dilated upon delivery.

Differentiating Gastroshiza from Other Abdominal Wall Defects

It is easy to confuse gastroshiza with other similar conditions, most notably gastroschisis and omphalocele. However, accurate differentiation is critical as the management, associated anomalies, and prognosis can differ significantly. The medical community sometimes uses the term gastroshiza to specify a defect where the stomach is the primary eviscerated organ, making it a specific subtype rather than a wholly separate condition.

The most common comparison is to gastroschisis. While both are full-thickness defects without a protective sac, classic gastroschisis typically involves the extrusion of the intestines. Gastroshiza, by its specific definition, involves the stomach. The size of the defect can also be a clue; the defect in gastroshiza is often smaller than that seen in a typical gastroschisis case because it only needs to accommodate the stomach. Omphalocele, on the other hand, is a fundamentally different defect. It occurs at the base of the umbilical cord, involves the herniation of abdominal contents (often liver and intestines), and is always covered by a protective membranous sac. Omphalocele is also far more frequently associated with other major genetic and chromosomal abnormalities.

Unraveling the Causes and Risk Factors of Gastroshiza

The exact cause of gastroshiza, like many congenital defects, is not completely understood. It is believed to be multifactorial, meaning a combination of genetic predispositions and environmental triggers likely plays a role. It is not typically considered an inherited condition in a straightforward Mendelian pattern; meaning, it doesn’t usually pass directly from parent to child in a predictable way. However, some research suggests there may be a genetic component that increases susceptibility.

Extensive epidemiological studies have identified several strong risk factors associated with abdominal wall defects, including gastroshiza. The most consistently observed risk factor is young maternal age. Mothers under the age of 20 have a significantly higher chance of having a baby with a defect like gastroshiza. Other potential risk factors include lower socioeconomic status, nutritional deficiencies, and the use of certain substances. There has been ongoing investigation into the role of vasoactive compounds, such as those found in decongestant medications (e.g., pseudoephedrine) and illicit drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine. These substances are thought to potentially cause vascular disruptions during critical windows of abdominal wall development, leading to the defect.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms of Gastroshiza

For the expectant parent, there are no physical symptoms or signs that would indicate a diagnosis of gastroshiza. The condition is entirely internal to the developing fetus and is not something a mother can feel. The first and primary way gastroshiza is identified is through prenatal ultrasound imaging. During a routine anatomy scan, typically performed between 18 and 20 weeks of gestation, a skilled sonographer or perinatologist may visualize the abdominal wall defect.

The key prenatal signs of gastroshiza on an ultrasound include the clear visualization of the stomach located outside the abdominal cavity, floating freely in the amniotic fluid. The defect itself, to the right of the umbilical cord insertion, may also be visible. Sonographers will also look for secondary signs, such as a dilated or thickened stomach wall due to its exposure to amniotic fluid. After birth, the diagnosis is immediately apparent and visual. The newborn will have a visible defect on the abdomen, and the stomach will be seen protruding through it. The exposed organ will appear reddish and may be inflamed or covered in a fibrous coating due to the chemical irritation from amniotic fluid exposure.

The Critical Role of Prenatal Diagnosis and Monitoring

Once a potential abdominal wall defect like gastroshiza is suspected on a routine ultrasound, the pregnancy is classified as high-risk. This triggers a cascade of specialized prenatal care designed to monitor the baby’s health and plan for a coordinated delivery. The parents will be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist, who will conduct a detailed, targeted ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis, assess the size of the defect, and identify exactly which organs are involved.

This detailed monitoring doesn’t stop at a single scan. Mothers will undergo more frequent ultrasounds throughout their pregnancy to track the baby’s growth, assess the amount of amniotic fluid, and closely observe the condition of the exposed stomach. They will also monitor for signs of bowel dilation or other complications. This vigilant prenatal surveillance is not just about preparation; it is proactive management. It ensures that the medical team—including neonatologists, pediatric surgeons, and nurses—is fully prepared to provide immediate, life-saving stabilization to the newborn the moment they are delivered. The goal is to turn a potentially chaotic emergency into a well-orchestrated plan of action.

The Journey of Delivery and Immediate Postnatal Care

The delivery of a baby diagnosed with gastroshiza is a carefully orchestrated event. It is almost always recommended to take place at a tertiary care center, a hospital with a Level III or IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and an on-site pediatric surgery team. This eliminates the need for a risky transport of a critically ill newborn after birth. The mode of delivery—vaginal or cesarean section—is usually determined by standard obstetric indications rather than the defect itself, unless there are other complicating factors.

The moment the baby is born, the clock starts ticking. The primary immediate goals are stabilization and protection of the exposed organ. The neonatal team will quickly suction the baby’s airways and ensure they are breathing effectively. Meanwhile, great care is taken with the exposed stomach. It is immediately covered with a sterile, non-adhesive dressing and the entire lower half of the baby’s body is placed in a clear plastic bowel bag or wrapped in sterile plastic wrap. This serves a critical purpose: it prevents rapid heat and fluid loss, which can be catastrophic for a newborn. An intravenous (IV) line is inserted to provide fluids, antibiotics, and pain medication. A nasogastric (NG) tube is also placed to suction out air and secretions from the stomach, preventing dilation and further complications.

Surgical Repair Options for Gastroshiza

Surgery is the only definitive treatment for gastroshiza, and the approach depends on the size of the defect, the condition of the exposed stomach, and the overall stability of the baby. The pediatric surgical team will evaluate the newborn and decide on the best strategy, which generally falls into one of two categories: primary repair or staged repair.

A primary repair is a single surgery performed shortly after birth. The surgeons carefully reduce the stomach back into the abdominal cavity and then suture the muscle and skin layers closed to complete the abdominal wall. This is often possible in cases of gastroshiza because the defect is smaller and only the stomach is involved, making it easier to fit back into the abdominal cavity. However, if the abdominal cavity is underdeveloped or too small, or if the stomach is significantly swollen, forcing it back in can increase pressure, compromise breathing, and reduce blood flow. In these cases, a staged repair is necessary.

The Staged Repair Process and Silo Use

When a primary closure is not feasible, the surgical team will opt for a staged repair. This is a more gradual process that allows the abdominal cavity to slowly stretch and accommodate the returned organ. The first stage of this process involves placing a protective silo over the exposed stomach. This silo is a pre-formed, spring-loaded silicone sack that is sutured to the fascial edges of the defect. The stomach is placed inside this protective pouch, which is then hung above the baby.

Over the course of several days, gravity gently assists in the gradual reduction of the stomach back into the abdomen. The surgeons or NICU staff will gently compress the silo daily, coaxing the organ deeper into the abdominal cavity. This slow process allows the baby’s abdomen to stretch and expand naturally without causing dangerous internal pressure. Once all of the contents are successfully reduced, the baby is taken back to the operating room for the final surgery: removal of the silo and formal closure of the abdominal wall. This method has dramatically improved survival rates for all abdominal wall defects.

The Complete Guide to Diag Image: Seeing Inside the Body to Revolutionize Healthcare

Navigating Potential Complications and Challenges

The journey for an infant with gastroshiza doesn’t end with the surgical closure of the defect. These babies are at risk for several short and long-term complications, necessitating careful and prolonged follow-up care. In the immediate postoperative period, the main challenges are related to achieving full intestinal function. The exposed stomach and the surgery itself can cause a temporary paralysis of the gut known as ileus. This means nutrition cannot be provided by mouth.

Therefore, babies receive all their nutrition intravenously through a line called a PICC (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter). This is known as Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN). While life-saving, long-term TPN use carries its own risks, including liver damage and serious blood infections. The major milestone in the NICU is the return of bowel function, signaled by stool output. Once this happens, feeding with breast milk or formula can begin very slowly and gradually advanced as the baby tolerates it. This can be a slow and frustrating process, often involving two steps forward and one step back.

Long-Term Outlook and Quality of Life

Despite the challenging start, the long-term outlook for infants born with isolated gastroshiza is overwhelmingly positive. With modern surgical techniques and advanced NICU care, survival rates exceed 90%. These children typically go on to live full, healthy, and normal lives. They participate in sports, go to school, and have no physical or intellectual limitations related to their condition.

The long-term follow-up for a child who has had gastroshiza repair is primarily focused on monitoring for gastrointestinal issues. Some children may experience persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which may require medication or, in very rare cases, further surgical intervention like a fundoplication. There is also a small risk of bowel obstruction later in life due to internal scar tissue (adhesions) from the initial surgeries. Parents are educated to recognize the signs of obstruction, such as persistent vomiting and abdominal pain. Annual check-ups with a pediatric surgeon or gastroenterologist are common during the first few years of life, but these often become less frequent as the child grows and proves to be free of complications.

The Emotional and Supportive Care for Families

A diagnosis of gastroshiza can be emotionally devastating for expectant parents. Feelings of fear, guilt, anxiety, and grief for the loss of a “normal” pregnancy are all common and completely valid. It is crucial for families to know that they are not alone and that these feelings are a normal response to an unexpected challenge. Building a strong support system is an essential part of the journey.

This support system should include the medical team, who can provide clear, compassionate, and honest information. Do not hesitate to ask your surgeons and neonatologists questions, no matter how small they may seem. Seeking support from other families who have been through similar experiences can be incredibly powerful. Organizations like the Avery’s Angels Gastroschisis Foundation provide resources, community connections, and advocacy for families affected by abdominal wall defects. Finally, seeking professional mental health support, such as a therapist or counselor familiar with medical trauma, can provide parents with the tools to manage their stress and anxiety, making them better able to support their new child.

Advances in Research and Future Directions

The field of fetal and pediatric surgery is constantly evolving, leading to ever-improving outcomes for conditions like gastroshiza. Research is ongoing in several key areas. Scientists are working to better understand the genetic and environmental causes of abdominal wall defects, which could one day lead to preventive strategies. There is also exciting research into fetal interventions, though these are currently more relevant for other conditions like severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Perhaps the most promising advances are in the realm of regenerative medicine. Researchers are experimenting with various materials and techniques to improve closure outcomes. This includes the use of biodegradable synthetic mesh that can help bridge a defect and encourage the body’s own tissue to grow over it, eventually dissolving away without a trace. Other areas of focus include optimizing nutritional support for these infants to prevent TPN-associated liver disease and refining surgical techniques to minimize postoperative pain and accelerate recovery. The future for babies diagnosed with gastroshiza is brighter than ever.

Conclusion

The path of a gastroshiza diagnosis is undoubtedly one few parents expect to walk. It begins with the shock of a prenatal ultrasound finding and quickly transitions into a world of medical terminology, surgical plans, and the beeping monitors of the NICU. However, as we have explored, gastroshiza, while a serious congenital defect requiring immediate specialized care, has an excellent prognosis. Through timely prenatal diagnosis, delivery at a high-level facility, expert surgical intervention, and meticulous postoperative care, the vast majority of these children not only survive but thrive. They overcome their challenging entrance into the world and go on to live lives completely unhindered by their initial condition. For families facing this diagnosis, knowledge is power. Understanding what gastroshiza is, what the treatment entails, and what the long-term future holds can replace fear with hope and provide the strength needed to support their resilient child through this journey.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is gastroshiza a genetic condition that could affect future pregnancies?

While the exact cause of gastroshiza isn’t fully known, it is not typically considered a directly inherited genetic disorder like cystic fibrosis or Huntington’s disease. Most cases are believed to be sporadic, meaning they occur by chance. However, there does appear to be a slight increased recurrence risk for abdominal wall defects in general within families. If you have had a child with gastroshiza, it is recommended to speak with a genetic counselor before a subsequent pregnancy. They can review your specific family history, discuss potential risks (which are generally low, often cited as 3-5%), and provide personalized guidance.

How long will my baby need to stay in the NICU after surgery for gastroshiza?

The length of the NICU stay for a baby with gastroshiza can vary significantly from one infant to another, but families should prepare for a stay of several weeks to a few months. The timeline is predominantly dictated by the baby’s ability to tolerate full feedings by mouth. After surgery, the gut is often slow to “wake up” (ileus). The baby will be on IV nutrition until their digestive system begins to function properly. Then, feeding is introduced very slowly and advanced gradually. Setbacks, such as feeding intolerance or vomiting, are common and can prolong the stay. The average stay can range from 4 to 8 weeks, but this is highly individual.

Will my child have a large, noticeable scar from the gastroshiza repair?

Yes, your child will have a scar on their abdomen from the surgical repair of the gastroshiza defect. The size and appearance of the scar will depend on the size of the original defect and whether the repair was primary or required a staged approach with a silo. However, pediatric surgeons are very skilled at minimizing and placing scars as discreetly as possible. Over time, the scar will fade and flatten. Many individuals who had abdominal wall defect repairs as infants view their scars as a badge of honor and a testament to their strength and resilience early in life.

Are there any specific activity restrictions for a child who had gastroshiza?

Once a child has fully recovered from their surgical repair and their surgeon has cleared them, there are typically no long-term activity restrictions. These children can and should participate in all normal childhood activities, including sports and rough-and-tumble play. The abdominal wall heals to be very strong. In the immediate months following surgery, your surgical team may advise caution with activities that put intense strain on the core, but this is temporary. The goal is for these children to live completely normal, active lives without limitations.

What is the difference between gastroshiza and gastroschisis?

This is a common point of confusion. The term gastroshiza is often used to specify a defect where the stomach is the primary organ protruding through the abdominal wall defect. Gastroschisis is the broader term for a defect to the right of the umbilicus without a protective sac, and it most commonly involves the small and large intestines. In many medical contexts, gastroshiza is considered a specific subtype of gastroschisis rather than a wholly separate condition. The importance of the distinction lies in the details of management; a protruding stomach might have different implications for feeding and recovery than protruding intestines, but the overall surgical principles of protection, reduction, and closure remain the same.