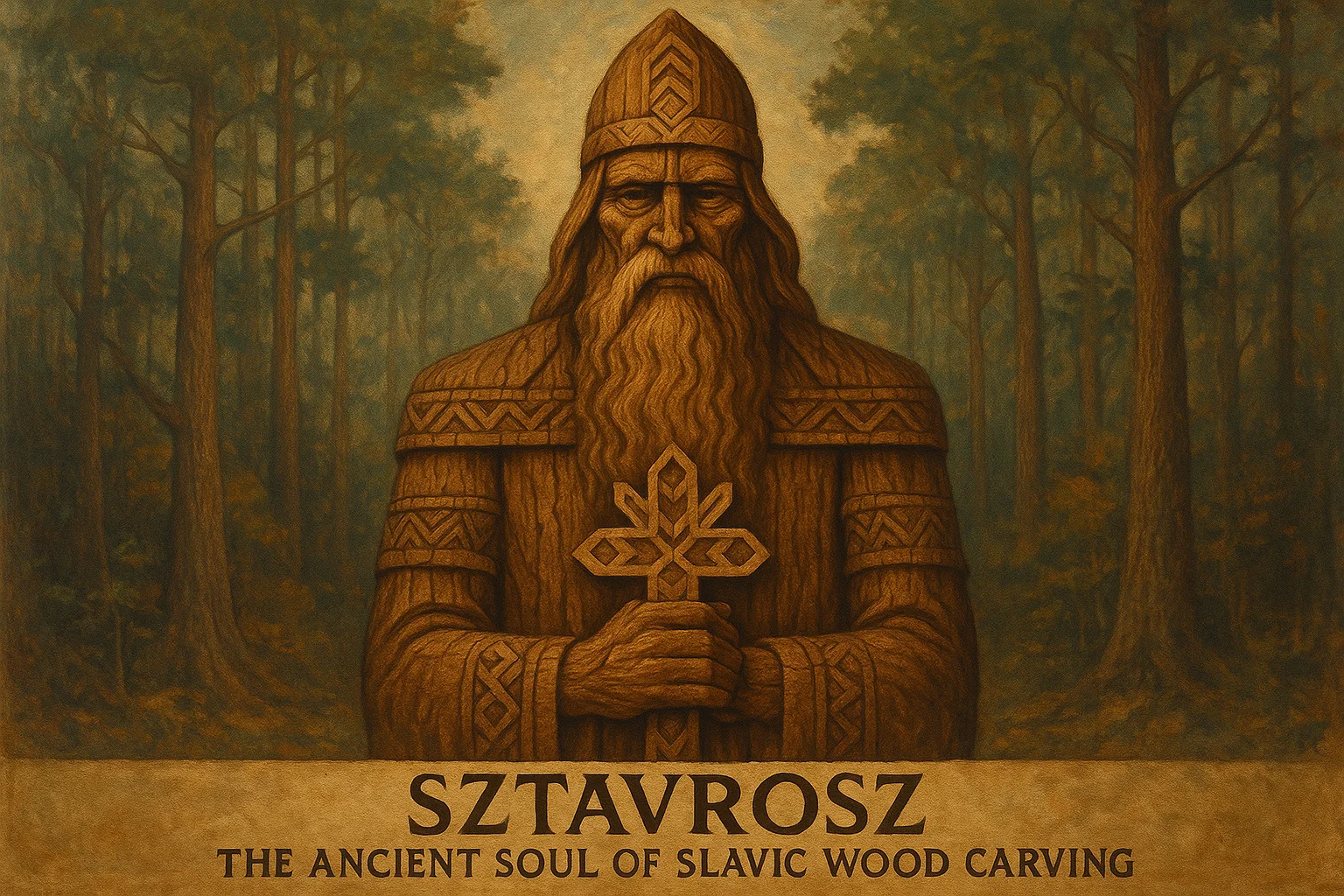

Sztavrosz: The Ancient Soul of Slavic Wood Carving

Imagine walking into an old wooden house, perhaps in the Carpathian Mountains or a quiet village in Poland. Your eye is immediately drawn to the eaves, the window frames, the central doorpost. They are not plain or merely functional; they are alive with form and shape. Intricate rosettes spiral like the sun, geometric patterns interlock in a dizzying dance, and stylized figures of animals and plants tell stories older than memory. This is not mere decoration; this is a language, a prayer, a protection carved in wood. This is the world of Sztavrosz.

Sztavrosz (often spelled in various ways like stavrosz or stawrosz, and originating from a word meaning “cross” or “crucifix”) is a traditional form of Slavic wood carving that goes far beyond simple craft. It is a folk art steeped in history, spirituality, and a deep connection to the natural world. For centuries, artisans used chisels and knives to transform ordinary beams, furniture, and household objects into extraordinary canvases of cultural identity. These carvings were believed to ward off evil spirits, attract good fortune, and serve as a constant reminder of the community’s beliefs and cosmology. Today, Sztavrosz is experiencing a renaissance, captivating modern woodworkers and cultural enthusiasts who are drawn to its beauty, depth, and the tangible link it provides to a rich ancestral past.

The Deep Roots and Historical Journey of Sztavrosz

To understand Sztavrosz is to take a journey back in time, to a period before mass production and digital distraction. Its origins are intertwined with the pre-Christian pagan beliefs of the Slavic peoples. Ancient Slavs were animists, meaning they believed that spirits resided in all natural elements: trees, rivers, stones, and the home itself. Wood, being the primary building material, was considered especially potent. Carving specific symbols into it was a way to communicate with these spirits, to appease them, or to harness their power for protection.

The motifs used were a direct reflection of this worldview. Solar symbols, like radiating circles and swastikas (a ancient symbol of the sun and eternity long before its modern appropriation), were carved to ensure the sun’s return each day. Fertility symbols, often depicting goddess figures or intricate plant life, were intended to guarantee a good harvest and healthy family. Figures of birds, horses, and wolves connected the household to the animal kingdom and the spirit world. With the arrival of Christianity in the Slavic regions, Sztavrosz did not disappear; it evolved. The art form was seamlessly incorporated into the new faith. Pagan solar symbols were reinterpreted as halos or the light of God. The ancient tree of life motif found a new parallel in the cross of Christ, and the name Sztavrosz itself, deriving from terms related to the cross, signifies this fusion. Carvings began to appear in and on churches, and the motifs expanded to include Christian crosses, saints, and angels, all executed in the distinct, stylized folk language of the carver.

The practice of Sztavrosz carving was predominantly passed down through generations within families and communities. It was not a formal art taught in academies but a living tradition. A young boy would learn by watching his father or grandfather, first handling the tools, then practicing simple cuts, and eventually being entrusted with carving a minor part of a new home’s ornamentation. This ensured the survival of specific styles and motifs unique to particular regions, from the delicate lace-like patterns of the Kurpie region in Poland to the bolder, deeper reliefs found in the Slovakian Tatra Mountains. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw a decline in this practice as industrialization made manufactured goods more accessible and urban living replaced traditional rural lifestyles.

The Symbolic Language Carved in Wood

At the heart of Sztavrosz lies a rich and complex symbolic language. Every cut, every pattern, every figure was intentional, serving a purpose far greater than aesthetics. These symbols formed a protective barrier around the home and its inhabitants, a visual incantation against the unseen dangers of the world. Understanding this vocabulary is key to appreciating the depth of this art form.

One of the most universal and important motifs is the Solar Symbol. Appearing as rosettes, wheels with spokes, or spirals, these symbols represent the sun deity, life-giving energy, the cycle of life, and the triumph of light over darkness. They were most commonly placed on the top of gables, the highest point of the house, to act as a beacon and to ensure the home was never without light and warmth. Another central symbol is the Tree of Life, a powerful motif representing the connection between the underworld (roots), the earthly realm (trunk), and the heavens (branches). It symbolizes fertility, ancestry, and the eternal cycle of growth, death, and rebirth. In a post-Christian context, it also came to represent the cross and the promise of salvation.

Animal motifs also carried profound meaning. Birds were seen as messengers between the world of humans and the world of gods, often representing the souls of ancestors. Roosters, with their crow heralding the dawn, were carved as protectors against evil spirits that were believed to be active at night. Horses symbolized strength, wealth, and the journey of the sun across the sky. Even plants held significance. The vine represented joy and eternal life, while flowers like the lily were symbols of purity and, later, the Virgin Mary. These symbols were rarely used in isolation. A master Sztavrosz carver would compose them into a harmonious narrative that covered the entire home, turning the structure itself into a sacred text written in wood.

The Essential Tools and Timeless Techniques of the Craft

The beauty of Sztavrosz lies in its accessibility. Unlike some crafts that require a vast array of expensive machinery, traditional Sztavrosz relies on a relatively simple set of hand tools, each serving a distinct purpose. The primary instrument is the carving knife. A sharp, sturdy, and well-balanced knife is the carver’s extension of their hand, used for making precise cuts, shaping details, and paring away wood. Next are the chisels. A basic set includes straight chisels for cleaning out areas, skew chisels for getting into corners, and most importantly, gouges.

Gouges are the workhorses of Sztavrosz. These are chisels with a curved cutting edge, and they come in a vast array of sweeps (the curvature of the blade) and widths. A #3 gouge has a gentle curve, while a #9 is a deep, U-shaped “veiner” used for cutting channels. A Sztavrosz artisan might use a small selection of just 5-7 gouges or a comprehensive set of over 30 to achieve every possible curve and hollow. A mallet, traditionally made of wood, is used to drive the chisels and gouges for deeper cuts and for removing larger areas of waste wood. Finally, a coping saw is useful for roughing out shapes, and sharpening equipment—a sharpening stone and strop—is absolutely essential, as a dull tool is dangerous and ineffective.

The techniques themselves are a dance between the carver, the tool, and the wood. The most common technique is relief carving, where the design is raised from a flat background. This can be low relief (bas-relief), where the projection is slight, or high relief, where the figures are almost fully in the round. The process almost always begins with transferring the design onto the prepared wooden surface using a template or freehand drawing. The carver then uses a combination of knives, chisels, and gouges to carefully “waste” or remove the background wood, leaving the design standing proud. Key techniques within this process include stop cuts (to define edges), paring cuts (to remove thin shavings), and stabbing cuts (to create deep points). The goal is to create a play of light and shadow, with the depth and angle of the cuts giving the two-dimensional design a dynamic, three-dimensional life.

Choosing the Right Wood for Your Sztavrosz Project

The choice of wood is not a mere practical consideration in Sztavrosz; it is the first step in the creative and spiritual process. Traditionally, carvers used what was locally available and known to be durable and easy to work with. The species of tree was also believed to carry its own spiritual properties. Softwoods were generally preferred over hardwoods for their ease of carving, especially for large architectural elements.

Linden wood (or basswood) is, without a doubt, the king of traditional Sztavrosz carving. It is a soft, fine-grained, and relatively even-textured wood that cuts like butter under a sharp tool, allowing for incredibly crisp details and smooth finishes. It has minimal grain pattern, which means the carving itself takes center stage without competition. For these reasons, it is the perfect wood for beginners and masters alike. Another popular traditional choice is pine. While slightly harder than linden and with a more pronounced grain, it is widely available and was commonly used for structural elements that were also decorated, such as door frames and roof beams.

Other excellent woods include butternut, which is similar to walnut but softer and easier to carve, and poplar, another soft, inexpensive, and readily available option. While hardwoods like oak, walnut, and maple can be used, they require much sharper tools and more effort to carve, making them less ideal for those starting their Sztavrosz journey. Regardless of the species chosen, the wood should be properly seasoned (dried) to prevent warping or cracking after the carving is complete. For practice, many modern carvers use blocks of kiln-dried linden, which ensures stability.

Table: Common Woods for Sztavrosz Carving

| Wood Type | Hardness (Janka Scale) | Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linden (Basswood) | 410 (Very Soft) | Very fine grain, easy to carve, minimal figure, soft. | Ideal for beginners, intricate detail work, and practice. |

| Pine | 380-420 (Soft) | Soft, pronounced grain, can be resinous, affordable. | Traditional structural carvings, larger projects. |

| Butternut | 490 (Soft) | Soft, straight grain, rich brown color, easy to work. | Decorative pieces where a darker wood is desired. |

| Poplar | 540 (Soft) | Even texture, greenish-brown color, very affordable. | Practice boards and painted projects. |

| Oak | 1,290 (Hard) | Very hard, prominent grain, durable, challenging to carve. | Experienced carvers only, for durable outdoor pieces. |

A Step-by-Step Guide to Your First Sztavrosz Carving

Embarking on your first Sztavrosz project is an exciting step into a world of creativity and tradition. While mastering the art takes a lifetime, creating a simple, beautiful piece is entirely achievable for a beginner. The key is to start small, be patient, and focus on enjoying the process of learning to speak through your tools.

Your first step is design and transfer. Choose a simple, classic motif. A small solar rosette or a basic geometric pattern is perfect. Avoid complex figures for now. Draw your design on paper, then transfer it onto your wood block. You can use transfer paper (like carbon paper) or simply go over the lines on the back of your paper with a soft pencil, place it on the wood, and trace over the design to imprint it. Next, secure your wood. It is crucial to clamp your workpiece firmly to a solid bench. This prevents it from moving and causing an accident, and it allows you to use both hands to control your tool. Never try to carve wood that is held only in your hand.

Now, the carving begins. Using your V-gouge or a small knife, carefully outline your entire design. This initial cut doesn’t need to be deep, but it should be precise. It establishes the boundaries of your pattern. The next phase is called “grounding” or “wasting”—lowering the background so your design stands in relief. Use a wider, flatter gouge for this. Make controlled cuts with the grain to prevent tear-out. Take your time; remove thin shavings, not chunks. Work your way across the entire background area until it is uniformly lower than your raised design. The final step is refining and detailing. Go back to your outlined design and deepen the lines where necessary. Use smaller gouges to add texture or detail to the raised elements themselves. Once you are happy with the carving, you can leave it raw, sand it lightly, or apply a finish like linseed oil to protect the wood and highlight the play of light and shadow in your cuts.

Podcastle AI Revolutionizing the Podcasting Landscape

The Cultural Revival and Modern Applications of Sztavrosz

For a time, it seemed that Sztavrosz might become a forgotten art, a relic confined to open-air museums and history books. However, the last few decades have witnessed a powerful and heartfelt revival. This resurgence is driven by a global yearning for authenticity, hands-on craftsmanship, and a reconnection to cultural heritage. People are seeking alternatives to impersonal, factory-made goods, and Sztavrosz offers a profound sense of meaning and connection that is hard to find elsewhere.

Modern practitioners of Sztavrosz are found all over the world, not just in its Slavic homelands. The internet has played a crucial role, allowing enthusiasts to share techniques, designs, and inspiration across continents. Online forums, video tutorials, and social media groups have created a vibrant global community of carvers who are learning, teaching, and pushing the boundaries of the tradition. This new generation respects the old ways but is not bound by them. They are adapting traditional motifs onto new objects: intricate jewelry, smartphone cases, modern furniture, and wall art that fits contemporary interiors. The spirit of Sztavrosz—the infusion of meaning and beauty into everyday objects—remains intact, even as its applications evolve.

This revival is also closely tied to the broader movements of folk art renaissance and mindfulness. The slow, deliberate, and focused nature of hand carving is a form of active meditation. In a fast-paced world, the act of sitting down with a piece of wood and a chisel forces a state of presence and calm. Each cut requires attention, and the repetitive motion becomes almost therapeutic. Furthermore, there is a growing appreciation for the skill and “human touch” evident in handcrafted items. Owning or creating a piece of Sztavrosz is a statement—a celebration of slowness, skill, and story in a mass-produced world.

“A piece of wood is not just a material; it is a story waiting to be told. The carver does not create the story alone but listens to the wood and guides the forms within it to the surface, joining a conversation that began with the first tree.” — Anonymous Polish Folk Artist

Preserving a Legacy: The Future of Sztavrosz

The future of Sztavrosz looks bright, but its preservation as a living tradition, and not just a historical curiosity, requires intentional effort. The knowledge of master carvers, many of whom are advanced in age, is an invaluable resource that must be documented and passed on. This involves more than just recording techniques; it means capturing the stories, the meanings behind the symbols, and the cultural context that gives the art its soul.

Educational initiatives are paramount. This includes formal workshops and classes offered by cultural organizations and skilled artisans, both in-person and online. It also includes informal learning—the kind that happens in community centers, woodworking clubs, and between family members. Integrating Sztavrosz into school art curricula can spark interest in a new generation, teaching them not only a skill but also about their own heritage or the heritage of others. Furthermore, supporting contemporary artisans is crucial. By purchasing their work or supporting their Patreon accounts and online shops, enthusiasts ensure that these skilled individuals can continue to practice and teach their craft, making it a sustainable vocation and not just a hobby.

Ultimately, the preservation of Sztavrosz is a task that falls to the community of carvers and admirers. It is kept alive every time someone picks up a gouge to practice a cut, every time a parent explains the meaning of a carved symbol to their child, and every time a modern home is adorned with a handmade piece inspired by this ancient tradition. The goal is not to fossilize Sztavrosz in a past era but to ensure its core principles—connection to nature, symbolic meaning, and masterful handcraft—continue to inspire and protect us, just as they have for centuries.

Conclusion

Sztavrosz is far more than an archaic woodworking technique. It is a vibrant, living testament to human creativity and spirituality. From its ancient, pagan roots as a form of spiritual protection to its beautiful synthesis with Christian iconography, and now to its modern revival as a mindful art form, Sztavrosz has continually adapted while retaining its core identity. It is a language of symbols that speaks of the sun and the seasons, of protection and prosperity, and of a deep reverence for the natural world from which it springs. The journey into Sztavrosz is a journey into history, into art, and into a slower, more intentional way of living. It invites us to pick up a tool, to feel the grain of the wood, and to add our own voice to an ancient, ongoing conversation carved in timber. Whether you are an experienced woodworker or a complete novice, the world of Sztavrosz is open to you, offering a unique way to create beauty, connect with tradition, and make something truly meaningful with your own two hands.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the basic meaning of the word “Sztavrosz”?

The term Sztavrosz finds its roots in Slavic languages, often connected to words meaning “cross” or “crucifix.” This points directly to the art form’s deep integration with Christian symbolism after the spread of Christianity throughout Eastern Europe. However, the practice itself predates Christianity, meaning the name signifies a later evolution where the ancient pagan carving traditions were seamlessly adapted to reflect the new dominant faith, with the cross becoming a central motif.

I’m a complete beginner. What is the easiest Sztavrosz motif to start with?

The best motifs for a beginner are simple geometric patterns and solar symbols. A basic rosette—a circle with a central point and radiating lines or spirals—is a classic Sztavrosz design that is forgiving to carve and teaches fundamental skills like making stop cuts, paring, and controlling a gouge. Straight-line geometric patterns, like zigzags or step patterns, are also excellent for practicing control and learning how to work with the wood’s grain without causing tear-out.

Do I need a huge set of expensive tools to start learning Sztavrosz?

Absolutely not. One of the beauties of Sztavrosz is its accessibility. You can begin with a very small set of high-quality tools. The essential starter kit includes a good carving knife for detail work, a single U-shaped gouge (perhaps a #7 or #9 sweep around 10mm wide), and a V-parting tool. With just these three tools, you can practice a wide variety of cuts and complete many simple projects. It is far better to invest in two or three sharp, well-made tools than a large set of poor-quality ones.

How is Sztavrosz different from other styles of wood carving like whittling or chip carving?

While all are forms of wood carving, they differ in technique and purpose. Whittling is generally defined as carving with just a knife, often using a single piece of wood to create figures in the round by removing shavings. Chip carving involves using a knife to remove small, geometric “chips” from a flat surface to create a pattern. Sztavrosz is primarily a form of relief carving. It uses a variety of tools (knives, gouges, chisels) to create a design that is raised from a background surface, and it is distinguished by its specific cultural and symbolic motifs rooted in Slavic tradition.

Where can I find authentic Sztavrosz patterns and designs for inspiration?

Authentic patterns can be found in several places. Many books on Slavic folk art and wood carving contain collections of traditional motifs. Museums, particularly open-air ethnographic museums in Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Romania, often have extensive collections of carved architectural elements that you can study and photograph. Online, image searches for terms like “Slavic wood carving,” “traditional Polish carving patterns,” or “Kurpie carving” will yield a wealth of visual inspiration. The key is to study the old patterns to understand the style before creating your own interpretations.